It seems like a no-brainer: We all reflect on our own experiences and apply that knowledge next time, don’t we?

We might do this in our day-to-day experiences such as learning how to ride a bike or touching a hot stove for the first time, but in education, we don’t use this tool often enough.

Reflection after an experience is a natural part of learning. https://sites.google.com/site/reflection4learning/why-reflect "What did I do well? What can I do better next time?" In the classroom an easy way to get students to reflect on their own learning (metacognition) is through journals. By writing down their experiences and reflecting on them, students move from the more abstract world of "Yeah, I would like to do better on my next test," to the more concrete world of goal setting.

As teachers we want students to reflect on what they learned, analyze why they made the mistakes that they made, and make the appropriate adjustments next time. We assume that this is an inherent ability in all of us and that students do this regularly: the reality is that students either don’t reflect on their own learning or come to the wrong conclusions.

Students who stay up all night studying for a test and fail it the next day might simply say to themselves, “Well, I better not stay up all night next time.” While in the short term this may be true (process-I need to devote more time to studying); they are missing out on the bigger picture, content (what they are studying) and how they learn best (method).

Another problem is how we as teachers present reflection as a tool to our students. An article that appeared in Educational Theory (2006) refers to common mistakes that many teachers make in students’ reflection including:

"…misinterpretations of the literature, equating reflection with thinking, and teachers pursuing their own personal agendas at the expense of learners."

According to Boud and Walker, solutions to this include:

"…not to blur the differences between personal and professional domains, to be precise in distinguishing between reflective and formal learning, to be clear about the context in which reflective activities take place, and to be honest about the aims of reflection."

A good place for students to begin their own reflective practices is after an assessment. But to be effective, reflective practices should be accompanied with goal setting.

If we take the above advice, we need to explain to our students that reflecting after a test is not just counting the number of questions that they got wrong, and goal setting is not just about “I got a C- on my essay and next time I want to get an A+.”

If we take the above advice, we need to explain to our students that reflecting after a test is not just counting the number of questions that they got wrong, and goal setting is not just about “I got a C- on my essay and next time I want to get an A+.”

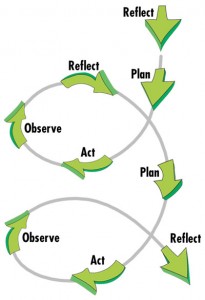

For students to reflect effectively, teachers should convey to their students that the process of reflecting is individualized (based on their own experiences and strengths) and involves planning.

Teachers can convey the importance and purpose of reflection (formal learning). They can model the process of reflection through a “think aloud” and can even have students share their own thoughts with each other in small groups. But in the end, the student’s reflection needs to be about how they themselves learn (reflective learning).

According to Boyd and Fales in the Journal of Humanistic Psychology (Spring 1983), Reflective learning is "the process of internally examining and exploring an issue of concern, triggered by an experience, which creates and clarifies meaning in terms of self, and which results in a changed conceptual perspective."

The context of student reflection should focus on their learning and not a just a quantitative analysis (“I got 10 wrong, I need to get 5 wrong next time for an A.”) nor a statistical analysis (“Most of the answers were ‘C’ so I should guess ‘C’ more often.”) As a teacher, I’ve heard both of these as the only legitimate analysis in the eyes of students; they would rather focus on external factors (the test or the environment) rather than on internal factors (themselves).

Begin with process. How much time do you give yourself to study? Where do you study best, in a quiet room? With music playing? Do you have a space in which you can study? How long can you concentrate on a difficult subject before you need to take a break?

Next, have students think about content. How you study for a math test vs. an English test? Does the test require rote memorization or a demonstration of a skill? Can you break down the test into skill questions vs. knowledge-based questions? Which kind did you have the most trouble with? Did the test require you to formulate an analysis? Or make an inference?

Last, have students think about what method of learning works best for them. Are they visual, kinesthetic, or auditory learners? Help them to think of ways to use their strengths and learning styles to their advantage. Flash cards may work best for some students, while rhymes or other mnemonic devices may work better for others. Students who need to memorize long passages or scripts might do well in recording themselves and listening to it multiple times.

By students reflecting on the process, content, and method of their own learning they can generate appropriate and specific goals before the next assessment. Putting these thoughts on paper is key. They can easily come back to their journals, review, reflect, and make adjustments for next time.

Finally, students’ reflections should not be graded. A check can be given that a reflective essay or journal was completed or general suggestions can be made such as, "Think about some specific steps can you take in order to be better prepared for the test next time." ; but we need to avoid the additional psychological burden that we would place on students by judging their own personal reflections.

Encourage your students to reflect often and effectively in their journey to become life-long learners.

Bret Thayer is a teacher with 15 years of classroom experience and is passionate about helping other teachers and students reach their highest potential…he also enjoys the Zen of fly fishing, cooking, and playing acoustic guitar.

References:

Procee, H. (2006), REFLECTION IN EDUCATION: A KANTIAN EPISTEMOLOGY. Educational Theory, 56: 237–253. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-5446.2006.00225.x

and , “Promoting Reflection in Professional Courses: The Challenge of Context,” Studies in Higher Education 23, no. 2 (1998)

Very good! Nice meet you at Twitter and read your blog. I have already place your site at my blog. Best Wishes,